“Storytelling is powerful – stories create change”

Dr Lina Fadel, a Syrian–British woman, mother and academic, sheds light on the stereotypes facing refugees and how we can all help address and combat these.

15.03.23

My journey in the UK started 17 years ago when I came to Scotland as a student. After finishing my studies, I was not able to return home to Syria because of the war that devasted my country.

What people often don’t realise is that the decision to stay here in the UK wasn’t an easy one. I came as a student and was proud of myself and my achievements. I could have returned home but I certainly wouldn’t have taken my son back to a country torn apart by war. No one in their right mind would risk their child’s life.

When I think about my life back in Syria, I remember how wonderful it was. I spent 24 years there and they were the best years of my life. Syria was a peaceful and safe country. The country’s multicultural, multi-ethnic and multireligious richness made it a great place to live in and dream of a good future.

© Lina Fadel

I grew up a free woman. I had an excellent education. My unorthodox and secular upbringing meant that I could live the life I wanted back home.

Staying here in the UK came with a lot of challenges. I had to prove that I deserved refuge and protection in the UK. I had no job, no support system and no family, but at least there was peace and a better future for my son. Staying here meant that I was fending for myself and trying to find a good life for my family. I’ve hit rock bottom and had to pick myself up so many times. With everything happening back home I was living in between worlds. I was neither fully here nor fully there, but parts of me were still at home. I was always trying to reconcile the two worlds.

I was also trying to belong and “integrate” – a word I am not very fond of. The thing about integration is that it’s often promoted as a one-way process while integration should be both ways; it’s not solely the refugees’ responsibility to integrate. Host communities should take a step towards the marginalised groups so that marginalised groups can take a step towards them and meet somewhere in the middle.

My experience has been that so many stereotypes and preconceptions are attached to immigrants and refugees, and I’m no exception. So many of these have been attached to me. Microaggressions such as, “were you liberated after you came to the UK?”, “you don’t look Syrian”, and “but you speak very good English” pointed to a toxic and reductive narrative that homogenises Syrians – all refugees – rather than seeing us as individuals with lives, careers, homes, children, hopes and dreams.

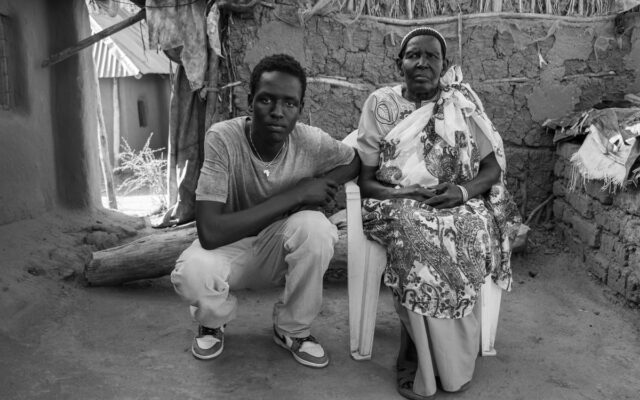

Last year, I witnessed these double standards first-hand when I spent a week volunteering in Calais with my partner. I was frustrated with the lack of empathy that the world has for refugees from the Middle East and Africa.

That’s why in my one-woman Cabaret of Dangerous Ideas show at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 2022, Become A Sexy Refugee in 5 Easy Steps, I wanted to expose the double standards that exist both at the UK border and in the media’s portrayal of refugees and address the discrepancy in the world’s empathy towards different groups of refugees.

Dr Lina Fadel performing her show “Become a sexy refugee in 5 easy steps!”

Dressed in a headscarf for my show, I stood on stage and asked: why is it that faces of displaced people like me do not elicit the world’s empathy like a fair-skinned face does? Why does the world respond differently to certain people? Is one war “sexier” or more appealing than another? Is there any human suffering more “deserving” of our compassion than another?

As a displaced scholar who used to be a refugee, this was my opportunity to speak out publicly about the injustices committed against migrants, refugees and asylum-seekers, and reflect on how we think and speak of them in our everyday conversations.

There are so many biases against and stereotypes about refugees. These stereotypes are about the way they look, speak, dress or even about their lives back home.

It’s important to remember that being a refugee is not an identity or a label but rather a temporary state, an experience. It really is a transition from one thing into another. It changes you. Anyone could find themselves in that position one day.

For refugees and marginalised groups to challenge myths and stereotypes, they need to be given a platform to share their stories and speak for themselves. Stories are a human right and a responsibility – but most importantly, stories are a privilege that the majority of refugees do not enjoy.

As an academic, I truly believe that storytelling is powerful; we should share our individual stories because they help challenge stereotypes and create change. By sharing my story on stage, I told the world a different story about refugees from the Global South and a different story about a displaced academic from the Middle East. My message was that we, too, are legal and deserving of the world’s good attention and empathy.

If people want to inform themselves about refugees, they need to listen to different stories, the refugees’ stories.

Volunteering and doing charity work is a great way to talk to people and hear their stories. It’s not enough to sit in front of the TV and watch the news because there are biases and hidden agendas that distort our perceptions of refugees and dehumanise them. Stereotypes won’t disappear unless people understand they are harmful.

I also encourage everyone to be researchers in their daily lives – you don’t have to work in academia.

It’s crucial to think critically about what you read or hear just to avoid any misinterpretation. We can all be guilty of repeating things we hear which can be stereotypes and prejudices. So, the next time we repeat something about refugees, let’s stop and think: do I truly believe this claim? Do I have evidence to support it? These small actions can change the harmful discussions around refugees and help humanise them.

—

Listen to Lina Fadel’s latest podcast on Combating Reductive Refugee Narratives here.

Visit this link to play our ‘2 Two Truths and a Lie’ game.