The torment of living under apartheid

Jackie shares her experience of fleeing South Africa after her live suddenly changed under the apartheid system.

17.10.22

© Ian Panelo

This Black History Month (and every month) we’re celebrating Black refugees, asylum seekers and their supporters. As told in her own words, this is Jackie’s story.

—

When I was growing up, the apartheid system in South Africa was getting stricter.

The government began segregating us in education, and I was classified as ‘coloured’. Previously, I had the same educational curriculum as white children, but that swiftly changed.

A family photo taken in December 1963 featuring Jackie (right) aged 16 and her siblings.

Under apartheid, there were not only restrictions on education, but also on jobs and where you could live, among other things. Given my parents’ backgrounds as Black South Africans, they protested.

Due to this, my father decided to secure his pension early and resign from his post as a deputy head teacher at one of the two high schools in my town of Port Elizabeth open to ‘coloured’ people, intending to apply for other jobs.

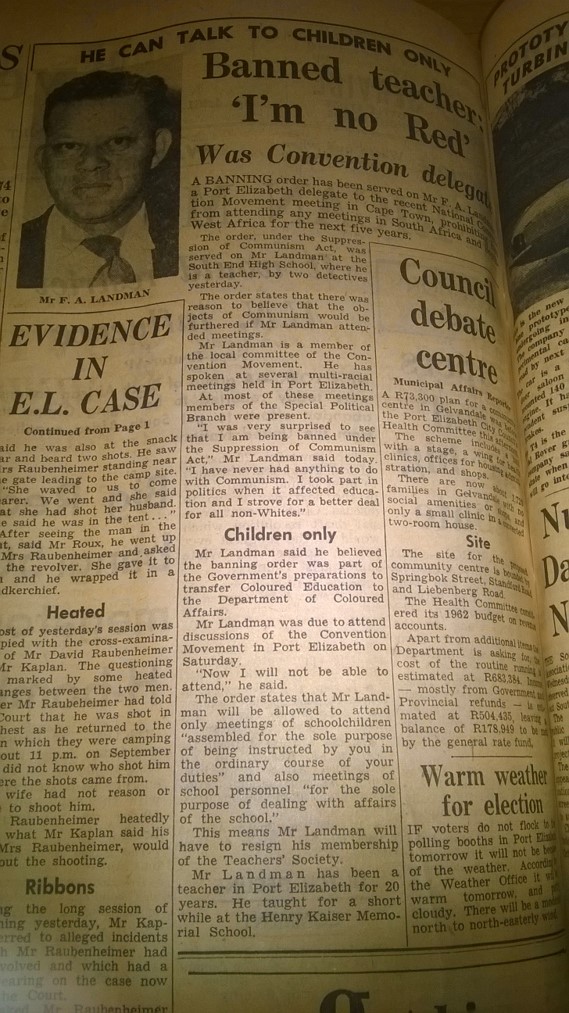

However, in 1961 my father was banned under the Suppression of Communism Act, and that banning order also specified that he could only attend meetings for purposes of teaching at the high school. He subsequently got a lawyer to explain that would mean no gatherings of three people.

I can still remember if anybody came to the house, I would always make tea so that it didn’t look like a meeting. We had the Special Branch (a South African security unit that enforced apartheid) coming to our home, turning it upside down and looking for anti-apartheid literature.

When he asked for permission to take up a new post, they said ‘no’ unless my father would give evidence against Nelson Mandela, as they were preparing a case against him at the time for the Rivonia trial. My father refused.

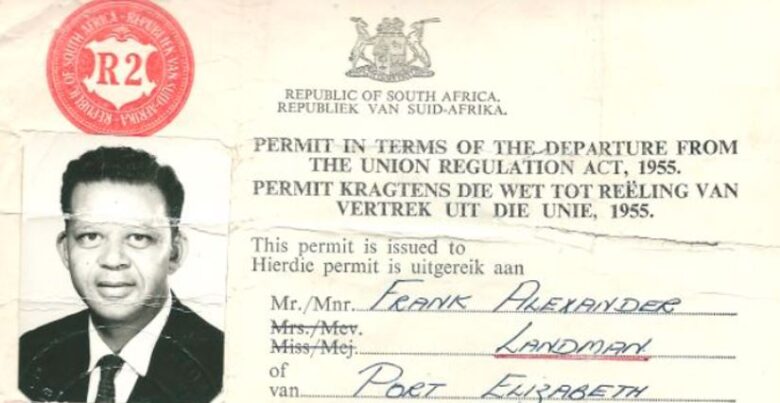

My father was then given an ultimatum – he could either give evidence against Nelson Mandela, or leave the country. Almost immediately, we received a letter from the Ministry of Justice stating that we should leave, and if we were still in the country after the specified date then we would be imprisoned. We were also warned that if we then attempted to return to the country we would also be imprisoned, once we were outside the country, we would receive no consular assistance. We would not get passports, only exit permit letters, one for my father and one for my mother that listed their three children by name.

An article in the Evening Post (a local newspaper) 14th October 1961 about Jackie’s father being banned from South Africa, including her father’s photo.

Luckily, due to my father collecting his pension early we were able to buy tickets to leave, going from Cape Town to Liverpool. We arrived in Liverpool on 28th February 1964, carrying with us only the exit permit letters that stated we were forced to leave. We were given Certificates of Identity in the UK, but my father was required to go to the police weekly to make sure they could keep track of us.

The first thing we did when we settled was to go and find a library. My father’s school never had one. Back in South Africa, there used to be some white people who would set up small libraries for the benefit of Black children – so I had at least seen what a library looked like and was able to show him how to use the catalogue and check out a loan.

As South Africa was a former Commonwealth country, my parents’ qualifications were recognised and they were able to get jobs in ‘educational priority areas’ – the poorest parts of London. Although it was difficult, we had the dignity of being able to pay our way and make a contribution.

By the time we were settled and found a place to stay, it was late in the school term, so I was forced to move down a year. The decision to leave was partially for my benefit, and this made me motivated to do well at school. I got a degree and had a professional life and I feel as though I’ve been able to contribute to society, just as my parents did.

Jackie’s father’s exit permit.

Despite this, it was still a culture shock arriving in the UK. Firstly, children didn’t know a lot about South Africa, with many children at my school being shocked that I spoke English. We also experienced racism, but as I was lighter-skinned, my darker-skinned brother would experience it more than me – he would get beaten up if he did not defend himself.

This racism continued into my adult life. I was often perceived to be ‘different’ and people had relatively low expectations of me. Having imposter syndrome is part of my life experience.

I was desperately sad when I found out that I wasn’t able to go back home. No refugee wants to leave their country – they do it because they feel they have no other choice.

If you could stand for a moment in my shoes, the risk of being imprisoned, being silenced, you’d understand why people leave. By helping them, you help us all to be who we want to be. You’d let us make the contributions to the society of refuge we can and want to make with dignity and pride.

—

To read more stories from people who have been forced to flee, please visit our website here.